SICP Goodness - From Pair to Flatmap (II)

Explore the power of list

Do you think Computer Science equals building websites and mobile apps?

Are you feeling that you are doing repetitive and not so intelligent work?

Are you feeling a bit sick about reading manuals and copy-pasting code and keep poking around until it works all day long?

Do you want to understand the soul of Computer Science?

If yes, read SICP!!!

Part I of this series can be found here.

Mapping over Lists

One extremely useful operation is to apply some transformation to each element in a list and generate the list of results.

(define (map proc items)

(if (null? items)

'()

(cons (proc (car items)) (map proc (cdr items)))))For example to take absolute value of each item in the list:

(map abs (list 1 -2 3 -4))

;; => (1 2 3 4)Trees

The item inside the list can themselves be lists.

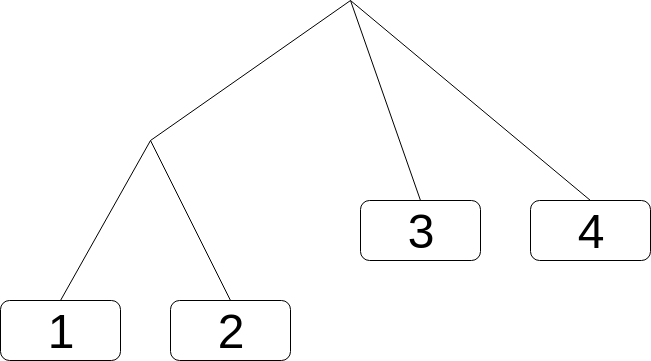

(list (list 1 2) 3 4)This can be seen as a tree structure.

Recursion is often very good at dealing with trees. For example, let’s implement a function that count the number of leaves in the tree.

-

Number of leaves of an empty list is 0

-

Number of leaves of an leaf is 1

-

Number of leaves of an list is the number of leaves of the

carplus the number of leaves of thecdr.

Here is the code.

(define (count-leaves x)

(cond ((null? x) 0)

((not (pair? x)) 1)

(else (+ (count-leaves (car x))

(count-leaves (cdr x))))))Mapping over Trees

We can now adapt our map function to work with trees. It has a very similar structure to the count-leaves function above.

(define (map-tree proc tree)

(cond ((null? tree) '())

((not (pair? tree)) (proc tree))

(else

(cons (map-tree proc (car tree))

(map-tree proc (cdr tree))))))

(map-tree abs (list 1 2 (list -3 -4)))

;;=> (1 2 (3 4))Sequence as Conventional Interfaces

If we use sequence (implemented as list in Scheme) as our primary data structure, then our program can be organized around the sequence operations. This can lead to moduler and clear design.

Let’s now examine 3 powerful sequence operations.

Filter

One common task is to filter a sequence to select only those elements that satisfy a given predicate.

This can be implemented easily as follows.

(define (filter predicate seq)

(if (null? seq)

'()

(if (predicate (car seq))

(cons (car seq) (filter predicate (cdr seq)))

(filter predicate (cdr seq)))))

(filter (lambda (x) (< x 3)) (list 1 2 3 4 5 6))

;;=> (1 2)Map

We have seen this already.

Accumulate

This operation essentially generate one value from running a function over the sequence with an initial value.

For example, let’s calculate the sum of a list of numbers.

(accumulate + 0 (list 1 2 3 4 5))

;; (+ 1 (+ 2 (+ 3 (+ 4 (+ 5 0)))))(define (accumulate op init seq)

(if (null? seq)

init

(op (car seq)

(accumulate op init (cdr seq)))))Notice that this version of accumulate starts at the end of the list. If you find that you want to start from the beginning of the list. You can use the following version:

(define (accumulate op init seq)

(define (iter seq result)

(if (null? seq)

result

(iter (cdr seq) (op result (car seq)))))

(iter seq init))Now we know how to implement filter, map and accumulate. Let’s combine them together. See the following example and see if you can understand it.

(accumulate max 0

(map (lambda (x) (* x 10))

(filter (lambda (x) (< x 10))

(list 2 3 7 6 5 4 8 9 5 6 10))))

;;=> 90Richard Waters(1979) developed a program that automatically analyzes traditional Fortran programs, viewing them in terms of maps, filters, and accumulations. He found that fully 90 percent of the code in the Fortran Scientific Subroutine Packages fits neatly into this paradigm.

Nested Loops

If you think of map is a kind of single loop over the list of data, then nested loops can be natually though as nested maps.

Let’s take an example.

Generate a list of pairs like ((0 0) (0 1) (1 1) (0 2) (1 2) (2 2) (0 3) (1 3) (2 3) (3 3) … (n n))

It is quite obvious that there must be some nested looping going on. The outer loop i is from 0 to n, and the inner loop j from 0 to i.

;; Generate a list from low to high

(define (enumerate-interval low high)

(if (> low high)

'()

(cons low (enumerate-interval (+ low 1) high))))

(define (nested n)

(map (lambda (x)

(map (lambda (y) (list y x)) (enumerate-interval 0 x)))

(enumerate-interval 0 n)))

;; (nested 3)

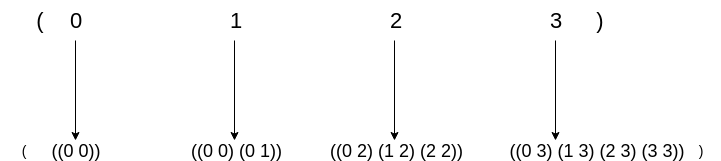

;; => (((0 0)) ((0 1) (1 1)) ((0 2) (1 2) (2 2)) ((0 3) (1 3) (2 3) (3 3)))The nested mapping process can be illustrated as follows:

This looks almost like what we want, except for the nested lists inside. What we want is a flat list, but what we get now is a list of lists. We need to flatten it.

We can use the accumulate function to achieve this:

(define (nested n)

(accumulate append '()

(map (lambda (x)

(map (lambda (y) (list y x)) (enumerate-interval 0 x)))

(enumerate-interval 0 n))))

;; (nested 3)

;; => ((0 0) (0 1) (1 1) (0 2) (1 2) (2 2) (0 3) (1 3) (2 3) (3 3))Turns out this map and then flatten the result is a common pattern. We can abstract it out into a flat-map function.

(define (flat-map proc data)

(accumulate append '() (map proc data)))Then we can rewrite nested using flat-map:

(define (nested n)

(flat-map

(lambda (x)

(map (lambda (y) (list y x)) (enumerate-interval 0 x)))

(enumerate-interval 0 n)))We have come to the end of this journey. We started with just a simple data structure pair, and all the way to quite advanced flat-map. We have hand crafted everything in between. Hope you enjoyed it as much as I do.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email